The empire tried to Russify Ukraine for centuries, instilling a sense of inferiority. This primarily occurred on the cultural front. The Russians rewrote history, banning the Ukrainian language and culture with the goal of annihilating Ukrainian identity and proclaiming themselves as the “elder brother” in the cradle of Slavic peoples. However, all propaganda crashes against the iron wall of historical monuments, archival documents, and scientific research.

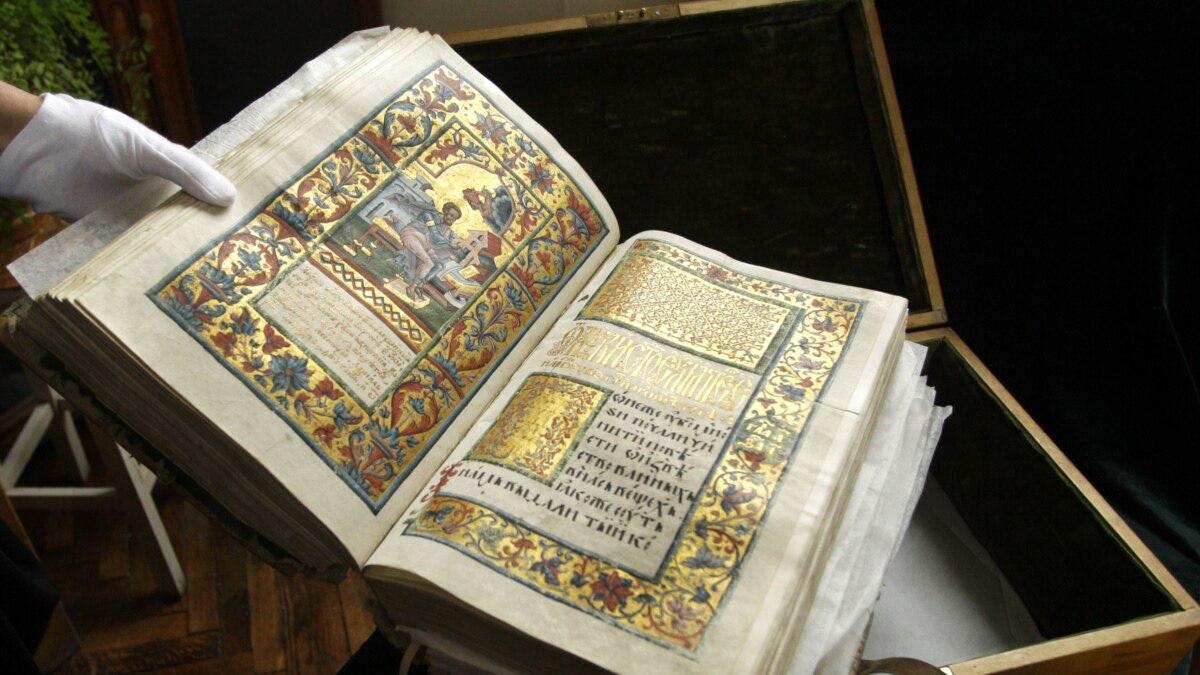

The Ukrainian language stems from a living folk spoken language that reached us in the XI century on birch bark letters. In contrast, the language of the Russian Federation comes from the artificially created conservative Old Church Slavonic. This language belongs to the South Slavic subgroup of Slavic languages. More precisely, it’s the Thessaloniki dialect of the ancient Macedonian language, in which Cyril and Methodius translated the Greek text of the Bible in the IX century. Having become the language of Slavic Orthodoxy, Old Church Slavonic also received the name – Church Slavonic.

Although there are significant phonetic differences between the “time-honoured” Old Church Slavonic and Church Slavonic. The same words are pronounced differently. The fact that Ukrainian was indeed the language of communication in the territories of Rus’ is evidenced by the fact that scribes, who worked on copying church and other books, often made mistakes and used Ukrainian words.

Now, in a broad temporal, territorial, and stylistic differentiation, the volume of the Ukrainian lexicon can reach 1 million words. At the same time, the Russian language, along with modern words and dialects, counts 400 thousand words. Also, any Russian word with a Slavic root can be derived from the Ukrainian language. But not every Ukrainian word can be derived using the Russian language.

Examples:

- the Russian language does not have the word “to clap” (in Ukrainian “pleskati”), but there is “to go dancing” (in Russian “idti v plyas” implying clapping);

- there is no word for “wash” (in Ukrainian “praty”), but there is “washerwoman” (in Russian “prachka”);

- you can also cite word formation with continuous exceptions to the rules – in Ukrainian “human-people-humanity” (“lyudyna-lyudy-lyudstvo”), in Russian “person-people-humanity” (“chelovek-lyudi-chelovechestvo”);

- problems with singular and plural – in Ukrainian “children-child” (“dity-dytyna”), in Russian “children-child” (“deti-rebyonok”), etc.

In addition, we cannot help but give an example of the well-known phrase “put all the dots over the ‘i'”, but where do they get the dots over the “i”?).

Soviet ideology significantly undermined traditional norms in various humanitarian spheres. This is especially true in the realm of language, as nothing identifies and materializes difference as much as language. Therefore, the philosophy of language, which was formed in the world practice and by Ukrainian thinkers, was greatly simplified by Soviet “scientists” to the absolutely utilitarian function, which was put into the formula “language = means of communication.”

This thesis was convenient for Russian ideologues because in the conditions of building a communist empire, language was considered only as a tool that would work in the system of Soviet construction. They also consciously ignored that language has much deeper functions. They are related to the impact on human consciousness, on her worldview, in the end, self-perception in this World, and on the generational and national memory.

All of this is encoded in sounds, words, phrases, and sentences. Through language, as if through optics, people perceive the World. All differences in language indicate a different perception of the World through language, different thinking, and different behavioral paradigm, which is formed by language.

Classic examples:

- “to win” (behind which is attached to human will – “can” or in Ukrainian “mogti”) and “to defeat” (in Russian “pobedit” – “after the trouble” – when the trouble itself will pass);

- “hospital” (where they “cure” or in Ukrainian “likuyut”) and “hospital” (in Russian “bolnitsa” – where they “are sick” or “boleyut”);

- “achieve success” (from “reach / reach” – trying to get something) and “achieve success” (in Russian “dobitsya uspekha”, related to “beat” or “bit”).

Through linguistics, national consciousness and identity are explored, because the features of a language determine the essence of mentality. Thus, the Russian language has an interesting grammatical property – the formation of impersonal constructions. That is, the action takes place by itself by an impersonal force in the absence of a subject. For example: “I signed a decree” (in Russian it’s phrased as if the decree was signed by itself with me being just an instrument), “we were blown away” (instead of “we went”).

Anna Wierzbicka (Polish and Australian linguist) in her work “Russian Language” evaluated this phenomenon: “The wealth and variety of impersonal constructions in Russian show that the language reflects and encourages the tendency prevailing in the Russian cultural tradition to view the world as a set of events that are not subject to human control or human understanding, and these events are more often bad for it than good.”

This phenomenon was strengthened, popularized among Russians and imposed on other nations during the Soviet era. Moreover, the Soviet regime deliberately changed the spelling, rules, grammar in the Ukrainian language for its maximum approximation to Russian.

Examples:

- it was “vakatsii” – it became “kanikuly” (holiday);

- it was “cinnamon” – it became “koritsa” (cinnamon);

- it was “osidok” – it became “mesto prebyvaniya” (place of stay);

- it was “velikiy viz” – it became “velika vedmeditsa” (big bear).

The development of impersonal constructions characterizes the mentality of the average Russian. Today we have the quintessence of depersonalization, expressed in the grammar of the Russian language, the grammar of absolving oneself of responsibility. The Soviet era cultivated teachings in which the subject turned out to be the point of application of some higher forces of history. He did not make decisions, but was grateful for wise guidance.

Alexander Peshkovsky (a Soviet linguist, one of the pioneers in the study of Russian syntax) noted: “Impersonal sentences, as we see, are not remnants of something dying out in the language, but on the contrary, it is what is developing and rooting more and more.”

In addition, the fact that processes in European languages evolve while in Russian there is a degradation of the language and, as a result, an increase in collective unconsciousness is confirmed by Anna Wierzbicka in her research work: “The growth of impersonal constructions and the displacement of personal sentences by impersonal ones are typical Russian phenomena. In other European languages, such as German, French, and English, changes usually go in the opposite direction. This gives us every reason to believe that the steady growth and prevalence of impersonal constructions in the Russian language correspond to the special orientation of the Russian semantic universe and, ultimately, Russian culture.”

Furthermore, approximately 10 years ago, a new part of speech emerged – the category of state. It is the predicate in impersonal sentences, indicating the state of a person or nature. It is externally indistinguishable from a verb or an adverb, but a verb is about human actions (e.g., “I was having fun”), and an adverb is about the quality of an action (e.g., “they took it cheerfully”). However, the category of state is about something unclear, someone unclear doing something unclear, and it’s not clear what has happened (e.g., “it was sad, it became worrisome, it will be scary”).

The transfer of responsibility for what is happening upward in the hierarchy finds clearer reflection in the language. The same tendency persists in relation to natural phenomena. During the Soviet Union era, weather forecast programs were particularly popular. This indicates a subconscious understanding that there was no truth in the Soviet epoch. The mass media lied. And, moreover, all troubles could be blamed on the weather rather than the result of one’s own actions. “It’s not that I’m sick, it’s that I am being sick” – the transfer of responsibility to something higher, the elimination of one’s own subjectivity.

In fact, for decades, a grammar of absolving responsibility was constructed – a grammar of the degradation of the Russian nation. Because everyone considers themselves instruments of higher forces that are beyond their control. This is the iron logic of Russia: belief in higher powers and the television that transmits the will of these forces.

Linguists and anthropologists tend to notice such peculiarities. After all, grammar, geographical location, form of government, public education, and so on, shape the national character. Russian culture has always glorified passive suffering, rather than active good deeds as a guarantee of spirituality. Individuality and initiative have always been persecuted. While any power is from God. The dogma of Peter I, which places power above God, is still adhered to today. Therefore, we see the desire of the political elite to restore the empire and live by the hypothetical Molotov pact – dividing zones of influence for world domination.

In conclusion, I would like to quote from Yuri Nagibin’s book “Darkness at the End of the Tunnel,” written in 1994: “People often ask themselves and each other: what will happen? Foreigners pose the same question to us with trusting horror. What will happen to Russia? Absolutely nothing. There will be the same uncertainty, instability, swamp, flashes of bad passions. That’s at best. At worst – fascism. Is this possible? The greatest guilt of the Russian people is that they are innocent in their own eyes. We don’t repent anything. Perhaps it’s time to stop pretending that the Russian people have been and remain the plaything of forces beyond their control? A comfortable, cunning, vile lie. Everything in Russia was done by Russian hands, with Russian consent, we sowed the bread ourselves, we soaped the ropes ourselves. Neither Lenin nor Stalin would have been our fate if we hadn’t wanted it.”